In a world where most of us can seemingly access products, entertainment, and loved ones in seconds with our devices, there is a major disparity in easy access to health care for a large portion of our country. Among many other issues, this limited accessibility is causing a discrepancy in how populations are represented in clinical trials, affecting health outcomes and treatments for various diseases.

There is not only interest from companies, but a critical need to improve the convenience and accessibility of clinical trials to people with diverse socioeconomic, ethnic, racial, and geographic backgrounds. This is because the diverse demographic representation of patient populations in clinical research is critical to ensuring therapies are safe and effective for all — not just for those who are able to attend a trial.

This important topic has always been top of mind for me throughout my entire career — especially as a woman of color — but I was inspired to vocalize the importance of diversity and inclusion after reading Janssen’s Best Practices for Diversity Success by Ed Miseta, Chief Editor of Clinical Leader. In it, Ed shares insights from Cassandra Smith, Director of Diversity and Inclusion in Clinical Trials at Janssen, surrounding the need for more understanding and planning by biopharmaceutical companies when it comes to conducting clinical trials with “empathy and humility.”

My experience with diversity in clinical care from day one

Much of my health care career has been dedicated to serving those who have unheard voices. As a young eye care doctor, my early clinic days were spent traveling between community health centers and seeing the vast array of cultures between neighborhoods just a few miles apart.

With each visit, the differences in patient education, pay, transportation, language, and culture astounded and humbled me. I began to learn new cultural norms, gained a new understanding and appreciation for different communities, and grew accustomed to new worlds.

This exposure to a diverse population helped me learn to adapt in order to build trust with patients. That meant learning how to say certain things, how to greet patients, how to speak to translators. I learned to design care for single mothers, for those without money for a co-pay, for those who travel four hours on a bus to see me, and for those with special needs.

I would come to work early to meet my non-English speaking patient to help him get a taxi to the hospital with notes in English to help translate the words the patient was unable to say. I'd give the patient notes for the taxi driver for drop-off at the hospital, notes for the security guard at the hospital on where to guide the patient, notes for the receptionist on who the patient is, notes for the physician on any disease findings, and notes that showed the patient's address to get home when the taxi comes. All because the patient was unable to communicate this himself, and each point of communication was a barrier to care. This was especially difficult for patients who not only had a language barrier but also had a visual impairment, urgent medical complication, or no family support.

For each new community, I listened and learned. I learned about the distrust of medicine, the fear of medical bills, and the countless barriers to care that stop a person from participating in health care programs. I spent time building a rapport and generating mutual understanding with individuals, which, in the end, allowed me to better treat and manage diseases. I had to be creative, resourceful, and ready to problem-solve and help patients reduce barriers to their care.

I came to the neighborhoods trained and ready as a great clinician but little did I know, block by block, the neighborhoods had so much to teach me. It still amazes me how no two clinics were the same even within a small geographic distance. Every community needs its own modification in care in order to reduce health disparities that cause lifelong cycles of diminished health options, opportunity, and outcomes.

Today’s gaps in diversity and inclusion for clinical trials (and why it’s important)

Since I have since made a transition from clinical care into the world of life sciences, you can imagine my surprise at the blanketed approach to clinical trials — this idea that one enrollment method, one registration method, and one protocol can be good enough for ALL people involved.

According to one report, the median percentage of African and African American participants per trial ranged from 1.8 to 3.5 percent. Asian participants represent an average of 0 to 7 percent, and for any group unspecified or not described as white, Black, or Asian was 1.4 to 3.4 percent.

That means at least 80% of all clinical trial patients are white, even when nearly 40 percent of Americans belong to a racial or ethnic minority.

Why does this discrepancy in representation matter? Some conditions for which trials are conducted affect certain minority groups more than others. In fact, a 2014 study in Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics found "variations in how people from different ethnic groups reacted to around 20 percent of new drugs approved between 2008 and 2013.”

For a more specific example, in 2018, Scientific American illustrated the discrepancy between conditions minorities experience and the patients who participate in those trials. “Americans of African descent are more likely to suffer from respiratory ailments than white Americans are,” the article states. “However, as of 2015, only 1.9 percent of all studies of respiratory disease included minority subjects, and fewer than 5 percent of NIH-funded respiratory research included racial minorities.”

We know communities are constructs of culture — diverse and multifaceted in their own way, with their own complex needs and communication styles. Learning to penetrate these communities to get the right data takes time, effort, money, and education. It takes movements of understanding on both sides to push innovation ahead.

How can we become more inclusive?

Fortunately, life sciences and pharmaceutical companies want to learn more about establishing trust and building relationships in the communities they serve. That is the first step in becoming more inclusive in clinical research and trials.

In order to foster more community involvement, we must focus on study design. We need to ensure that more minority populations are able to participate in studies with a health benefit to them. This can be done by including local community members of the populations represented in the study design process.

Another way our industry can become more inclusive and accessible is by decentralizing the clinical trial process. “New technologies that foster the decentralization of clinical trials may also offer opportunities for increased access for African Americans as well as other minorities not currently well represented in clinical trials,” a 2018 Nature report stated.

Decentralization of trials essentially makes it easier for populations to access health care and participate in clinical research, eliminating the need for a single research site. By allowing flexibility in clinical trial assessments to integrate seamlessly with daily life (at work, at home, or on the go), clinical trials have an opportunity to capture data from a larger, more diverse group of trial subjects.

When minority populations are accurately represented in the research, community health care providers can make confident treatment decisions based on science — as opposed to data extrapolation, assumed efficacy, and, sometimes, hope. Decentralized, customizable data capture that accounts for unique community needs is a critical part of making health care accessible and equitable for all.

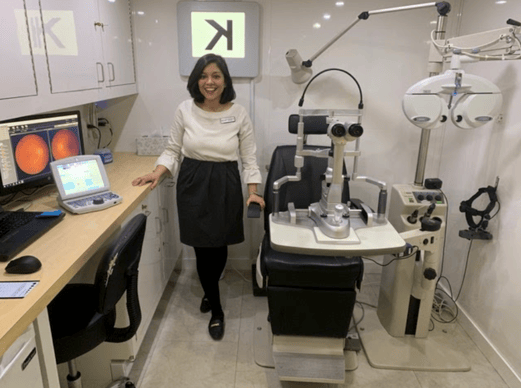

How 2020 On-site is working to improve access to care for all

2020 On-site was founded on the promise of bringing more accessible, patient-centered vision care to our communities. While we are always improving our systems and recognize we have a long way to go, we take pride in our team’s commitment to reaching underserved patients and diversifying our approach. By expanding our services into life sciences and biopharmaceuticals, we hope we can assist other clinical research companies to do the same.

A few ways we are working towards a more diverse and inclusive environment include:

- Lifting the geographic barriers of travel by bringing care directly to the patient

- Customizing vision care options to populations of interest

- Asking questions when working with new research sites about any special patient demographics such as language, accessibility, local customs, practices, preferences, modes of communication, and education

- Serving areas with low internet access and providing workarounds for trial subjects who may have difficulty with computer literacy

- Providing flexibility in scheduling options for trial subjects

- Reflecting local cultures in marketing materials

- Utilizing a bilingual staff and keeping translation devices onboard our mobile vision clinics to help improve communication

- Hiring doctors local to the region that we are serving who understand the community members best

With that in mind, we are always striving to break down barriers to access. Some of our key areas of focus in the months ahead include:

- Creating face-to-face interactions with remote services between the investigator and trial subjects in order to facilitate improved communication and trust

- Building tailored web pages for registration

- Focusing on a more diverse 2020 On-site employee recruitment strategy to ensure that we continue to have diverse opinions at the table as we expand and grow into our clinical trials operations

Conclusion

We can no longer depend on the traditional, one-size-fits-all approach to health care. Patient lives are complex, and research has to tailor to these complexities in order to retrieve data that is accurate and inclusive.

Health care and pharmaceutical companies must begin connecting with communities and create a trusted platform for which data is shared in both directions to make treatments that are safe for all. The approach must be deliberate, thoughtful, and come from a place of empathy.

To allow flexibility, variation, and diversity into clinical research is a daunting task. Repeatability and reproducibility have often been the comforting cornerstone of science. I’m hopeful that there are other innovators out there who see the work ahead and look forward to the challenge.

I would love to continue the conversation about inclusive, thoughtful, patient-centered clinical trial design. Reach out to me directly at dsarma@2020onsite.com and connect with me on LinkedIn.

About Dr. Debi Sarma

Dr. Debi Sarma is a residency-trained community health optometrist. She has built a career around vision health education and is passionate about improving access to vision care for those in need. Dr. Sarma has a Bachelor of Science degree from the University of Waterloo, as well as a Doctorate degree from the New England College of Optometry. She is a seasoned lecturer on disease topics and loves connecting with people to talk about innovation, culture, and leadership in healthcare.

Dr. Debi Sarma is a residency-trained community health optometrist. She has built a career around vision health education and is passionate about improving access to vision care for those in need. Dr. Sarma has a Bachelor of Science degree from the University of Waterloo, as well as a Doctorate degree from the New England College of Optometry. She is a seasoned lecturer on disease topics and loves connecting with people to talk about innovation, culture, and leadership in healthcare.